As I get this ready, it’s a very foggy day here in the UK. You’d think it was Silent Hill out there! It’s a nice break from the horrid humidity, though.

I’ve been playing plenty of games lately, and my 2022 GOTY series is ramping up. Right now, I have over thirty games battling it out for a spot in my Top 10 list so far, and I haven’t got any guaranteed candidates yet! For the struggles with development this year and all the delays, I’ve been happy with this year’s releases. For someone who enjoys a wide range of games, it’s been a good year.

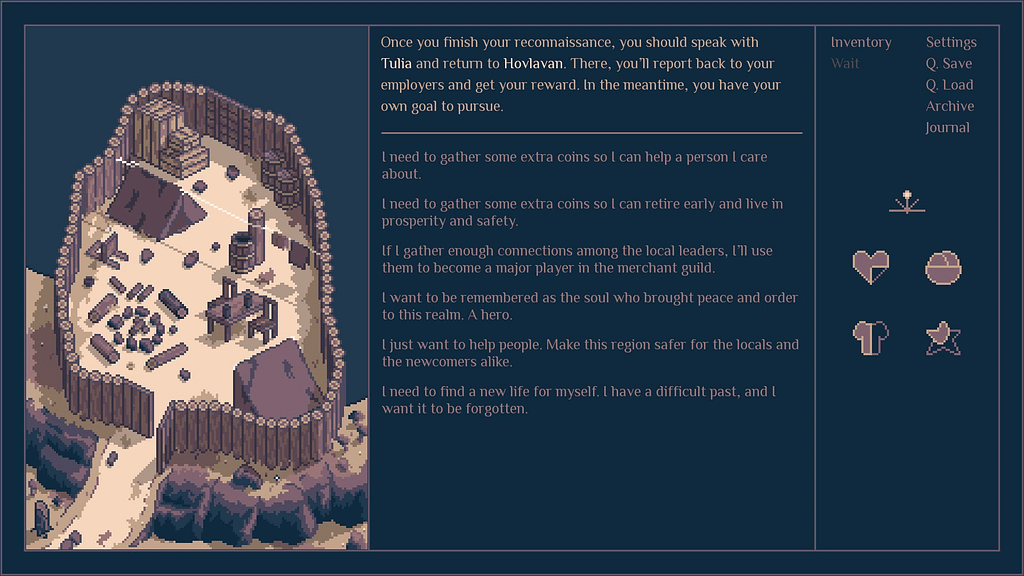

Today I bring an interview from Moral Anxiety Studio, the developer of Roadwarden. This impressive text-based RPG has a mountain of lore and immersive features packed into it, and I was honored to receive a review code for the game. I had plenty of pleasant conversations with these guys, and I wish them luck for their launch! Roadwarden should release the day this interview goes live. Here’s a link to the Steam page:

https://store.steampowered.com/app/1155970/Roadwarden/

First of all, tell me about yourself! What do you do?

Hi, and thanks for having me! I spent the last few years working on small video games. The first one I’m really proud of, Roadwarden, started as a humble project that most people would describe as an adventure game, but as the time went on, I needed to add more systems to it, stepping into the “RPG” label. But since I love RPGs, I’m not too sad about it.

While working on Roadwarden, I write, draw, code, and design.

What does being a game designer actually mean?

I feel like the dictionary definitions of the phrase are on point, but personally, I find great enjoyment in seeking ways to express experiences, moods, or ideas through gameplay. I used to be obsessed with making tiny tabletop RPGs that were firmly based in some sort of distinct cultural template. One was meant to replicate the surreal, outdated feel of the old Arthurian legends; one that was all about playing a lone, famous minstrel; one was about playing a large group of cannon fodder characters trying to survive the whims of NPC-adventurers.

Translating these stories, and the ways the society at large imagines them, into systems is fascinating. It takes bending limitations of the medium and deciding what should be expressed by the rules to keep the spirit of the source, and what ought to be omitted or removed.

And to me, it’s the same thing with Roadwarden. The game introduced combat when I decided it needed combat. It introduced simple survival systems when I decided it suffers from not having them.

There has been a great deal of controversy in recent years about microtransactions in gaming. Not so much an opinion, but why do games tend to cut out content to sell later as DLC and lootboxes? Is it to do with development costs? Or is it time related?

I originally wrote a long answer, but honestly, my knowledge of the business side of things is simply too limited. Yes, sometimes there are money-grabbing heads of companies who want to push NFTs for a quick rug pull, but usually there’s a more complex story happening behind the curtain. Trying to compensate for the losses from the previous game and hoping to gather enough savings to pay for the next one down the line; being forced by a producer or the mother company and acting against developers’ intent or goals; or being threatened by shareholders with a lawsuit for not utilizing the opportunity to gather more income. There’s no single answer that would explain all the possible sources, and saying something like “oh, it’s because of capitalism (bad)” won’t help anyone harmed by these issues. Thankfully, there are people and agencies who push for solving the most exploitative parts of the industry.

Tell us about your current project.

The pitch I use is “it’s an illustrated text-based RPG in which you explore and change a hostile, grim realm.” Roadwarden is my attempt at making a game that focuses on the things I like in RPGs the most, and that limits the significance of the things I either dislike, or only tolerate. For example, I hate grind, and I find pointless, repetitive violence to be extremely boring. I try to invite those of us who’d enjoy the dense mood of a realm that doesn’t really want an outsider to meddle with the course of things, or who enjoy getting to know complex NPCs.

As many developers, I’m fascinated with games that react to the player’s actions. While Roadwarden may be seen suffering from low production value, considering it’s mainly text, illustrations, and music, these limitations gave me a lot of freedom when it came to introducing minor and major changes to the game’s setting, as well as branching quests. I strongly believe every player will have a meaningfully different, unique experience.

As anyone who creates anything, we must all deal with criticism from consumers. How do you go about it particularly in the prolific and viral standard of gaming today?

Being an obscure, irrelevant person surely helps, as most feedback I get is from people engaged enough with my work that they’d rather express their enjoyment with what they experienced. However, I found ways to deal with negative feelings caused by criticism. When I was a teenager, I needed feedback to improve my writing, and I learned that having a good sleep, or at least a few hours to clear my mind, helps me handle criticism better. Whenever an opinion causes my negative emotions, I step back and don’t act upon them. Once I get calm, it’s much easier for me to find value in the received criticism. And to express my gratitude for receiving it.

Another thing is to learn that not every negative opinion is valuable or requires action from us. Instead of trying to satisfy everyone, it’s better to seek patterns in many comments and opinions. A person saying that something “is boring” may be just someone with a completely different taste and expectations. But after the same claim gets repeated multiple times in various places, it may be better to start investigating the cause.

What advice would you give budding developers into taking the plunge into game design?

I’d rather not give any, for most people wouldn’t consider my results successful or worth replicating, but I’d like to state this: being an artist who follows just their guts and dreams doesn’t work for most people, and usually ends up in defeat. There’s nothing wrong in releasing basic games exploiting popular genres for larger audiences and providing for one’s family, or for one’s employees and coworkers. In a world where most of us aren’t offered a free safety net, we need to accept that for most people designing and developing games won’t be a tool of honest, artistic expression, but rather a job, or a career. No side of the coin makes a “more real” designer.

If you still have time to play video games, what are some of your favorite ones to play?

I usually have one background game I waste my time on when I’m too exhausted to think. Currently it’s Slay The Spire, it’s just pure fun with crashing disappointments and triumphant highs.

Other than that, I tend to play small, short games that offer something unique, usually artsy indie titles. I can’t say I fall in love with all of them, but that’s just fine – I like them to widen my perspective and make me wonder what’s possible in the design landscape, and I don’t play video games solely for entertainment. I like art that challenges me.

Also, and I don’t understand why, RPGs make my critical brain turn off, for the most part. I tend to be very forgiving when I play them, usually entering a completionist goblin mode. I walk around finishing tiny tasks and quests, getting bored for 30% of the time I’m playing and listening to podcasts during repetitive combat encounters, and then I’m still like “that was great, I hope there will be a sequel”.

What inspires you to do what you do?

I crave communication, especially an intimate, friendly one, free of social conventions and small talk. At the same time, I was always obsessed with consuming a lot of art, and what happens is I start to ponder how it would be to express myself through the same medium. As a child, I read a lot of fantasy novels, so I wanted to be a writer. In my late teens, works of a specific poet touched me deeply, so not only I started to write a lot of poems, I went to a university studying literature and language. After I got obsessed with tabletop RPGs, I wanted to make them too. But for many, many years I knew I’d love to make video games, I just assumed I’d never have an opportunity to do so. I’m glad I was wrong.

What is the hardest part of your job?

The money. Dealing with the fact I made some bad games in the past. And tying my value as a person to some digital piece of art I made – definitely not a healthy approach.

What was your favorite thing about game development? Is there anything you find difficult or challenging in dealing with the struggles?

Since so far I’ve been mainly a solo-dev, I have the luxury of jumping between various tasks, which does wonders for breaking routines and avoiding boredom. However, the coolest part is always designing the new area, especially one with its own set of characters. Building connections, lore, unique interactions, quests with choices, both the obvious and the hidden ones.

Usually, the challenge hits when I have to cover this skeleton with actual meat. Writing is great, but I’m one of the so-called intuitive types, who enjoy exploring as they create, not knowing where it’s all heading. This is how I started my work on Roadwarden. But after some time, I no longer had a luxury to do so – I had to finish things, not open new ones. So I often knew exactly what I needed to do and how I wanted it to look, and the process of sitting down and writing lacked exploration and the joy it brings.

What lessons have you learned from your first game?

That I’m much worse at it than I thought I would be, considering how toxic I used to be criticizing the work of others. And that making games is much more difficult than it seems from the outside. And that it’s probably not a good idea to make a game while you are in the depths of depression.

Roadwarden is my third game. It feels insane to me that all of my projects were made by a single person – I just changed so much over the years I spent with them.

What are your future project(s)?

First I need to know what the reception of Roadwarden is. I can’t work on another game if it turns out to be a flop. I’ll need to move on.

I’m tired of spending months upon months on making a game on my own, having hardly any input from other people. I’d like to make a game with a small crew that would challenge me and either make me reconsider my vision, or adapt to the work of others. It would be great to be a writer or a quest designer for a large RPG.

My biggest dream would be to make another “slow” game, but one that’s more oriented on having a team of adventurers, instead of a single traveler.

If you couldn’t be a game developer, what ideal job would you like to do?

I’d like to stay close to art, especially one set in fantasy settings. An example of a dream job that’ll likely never be available to me would be a worldbuilding consultant.

What is your ideal video game if money and time was no object?

I’d like to push the boundaries of an “introspective”, immersive, reactive RPG beyond what we know, with as little padding and grind as possible.

Links I’d like to promote: